On Nov. 7, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral argument in United States v. Rahimi. Here’s what you need to know about one of this term’s most important cases.

The key question in Rahimi is this: Can the government prohibit domestic abusers subject to restraining orders from possessing firearms?

The Supreme Court will be ruling on whether an important part of current federal law—which prohibits people subject to domestic-violence restraining orders from possessing firearms—violates the Second Amendment.

Access to a gun makes it five times more likely that a woman will die at the hands of a domestic abuser, and every month, 70 women are shot and killed by an intimate partner. Nearly 1 million women alive today have reported being shot or shot at by intimate partners.

Guns in the hands of abusers not only increase the risk that victims will die, but are also a tool of intimidation—restricting the freedom of women and families, and forcing them to live with fear. If the Supreme Court upholds the Fifth Circuit’s decision, they will strike down the federal law prohibiting domestic abusers subject to restraining orders from owning firearms.

This decision is life or death for the millions of women, families, and communities across the U.S. who are impacted by the crisis of domestic violence—including the widespread use of guns by abusers.

In December 2019, a man named Zackey Rahimi allegedly assaulted his ex-girlfriend, identified in the case by her initials, C.M. According to the government’s brief, Rahimi threatened to take away the child they shared. He then knocked C.M. to the ground in the parking lot where they were arguing, dragged her to his car, and shoved her inside—hitting her head on the dashboard in the process.

After realizing that a bystander had seen this assault, Rahimi took out a firearm and shot at the bystander. Rahimi also threatened to shoot C.M. if she told anyone about the assault.

In February 2020, after a hearing in which Rahimi appeared, a Texas state court granted C.M. a two-year protective order from Rahimi. The court issued the order after it found that Rahimi had “committed family violence” and that this violence was “likely to occur again in the future.”

But although Rahimi participated in the hearing and signed an acknowledgement that he had “received a copy of this protective order,” he ignored it. While prohibited by the protective order from having guns or approaching C.M., he allegedly:

- Approached C.M.’s house in the middle of the night;

- Threatened another woman with a gun; and

- Fired a gun in five separate incidents in the span of two months.

During a search of his home, police found magazines, ammunition, two guns, and a copy of the protective order prohibiting Rahimi from having firearms.

As a result, a federal grand jury indicted Rahimi and he pleaded guilty and was convicted of violating the federal law that bars abusers subject to protective orders from possessing guns.

No. Under 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(8)—the law at the heart of the Rahimi case—three conditions must be met:

- A court must have issued the order after notice and a hearing at which the person subject to the order had an opportunity to participate;

- The order must forbid the person subject to the order from harassing, stalking, or threatening an “intimate partner,” the person’s child, or an intimate partner’s child; and

- The order must find either that a person poses a credible threat to the physical safety of a partner or child, or the order must explicitly prohibit the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the partner or child.

For purposes of this law, “intimate partner” of a person subject to a domestic violence protective order is defined as:

- A current or former spouse;

- A person with whom they share a child; and/or

- A person who cohabits or has previously cohabited with them.

Before pleading guilty, Rahimi moved to dismiss the criminal charges against him, arguing that 18 U.S.C. 922(g)(8) violates the Second Amendment. The district court rejected that argument because controlling, pre-Bruen case law had upheld 922(g)(8) as constitutional. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals originally affirmed for the same reason.

But after the Supreme Court ruled in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, the Fifth Circuit reopened Rahimi’s case and reversed its decision. The court said that, although Rahimi was “hardly a model citizen,” the government could not constitutionally disarm him on the ground that he was subject to a protective order.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Bruen, among other things, introduced a new historical test for evaluating Second Amendment cases that requires the government to establish that a challenged gun law is “consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.”

Judges must decide whether our current laws are analogous to historical laws and tradition ranging back as many as 150 to 250 years ago. Because laws specifically disarming domestic abusers didn’t exist in the 18th century, the Fifth Circuit effectively reasoned, Rahimi’s conviction could not stand. And their ruling applies not only to Rahimi, but to any domestic abuser subject to a protective order in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. If the Supreme Court decides to uphold that ruling, they will expand its reach to the entire country—and domestic violence victims nationwide will lose a core protection against gun violence.

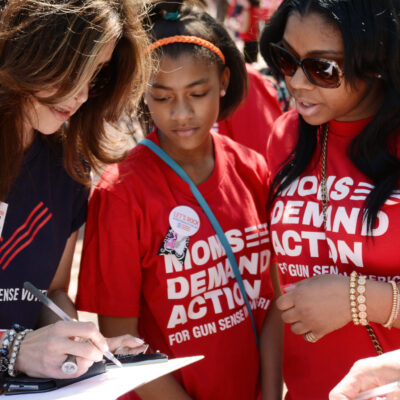

Everytown, alongside a coalition of domestic violence and gun violence prevention groups, called on the Supreme Court to take up the case. When the Court agreed to do so, Everytown filed a brief urging the Supreme Court to reverse. The Fifth Circuit misapplied Bruen by effectively requiring the government to identify identical historical laws. Instead, it should have recognized that the Second Amendment allows the government to disarm people who are not law-abiding, responsible citizens—and the Supreme Court must now act to reverse its dangerous decision.

Join us at the Supreme Court of the United States on Tuesday, Nov. 7 at 8:30 a.m. to call on the court to defend the lives of domestic violence survivors.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 800-799-SAFE (7233), available 24/7, for confidential assistance from a trained advocate, or text START to 88788 from anywhere in the U.S.

You can also find more resources on legal assistance in English and Spanish at WomensLaw.org.