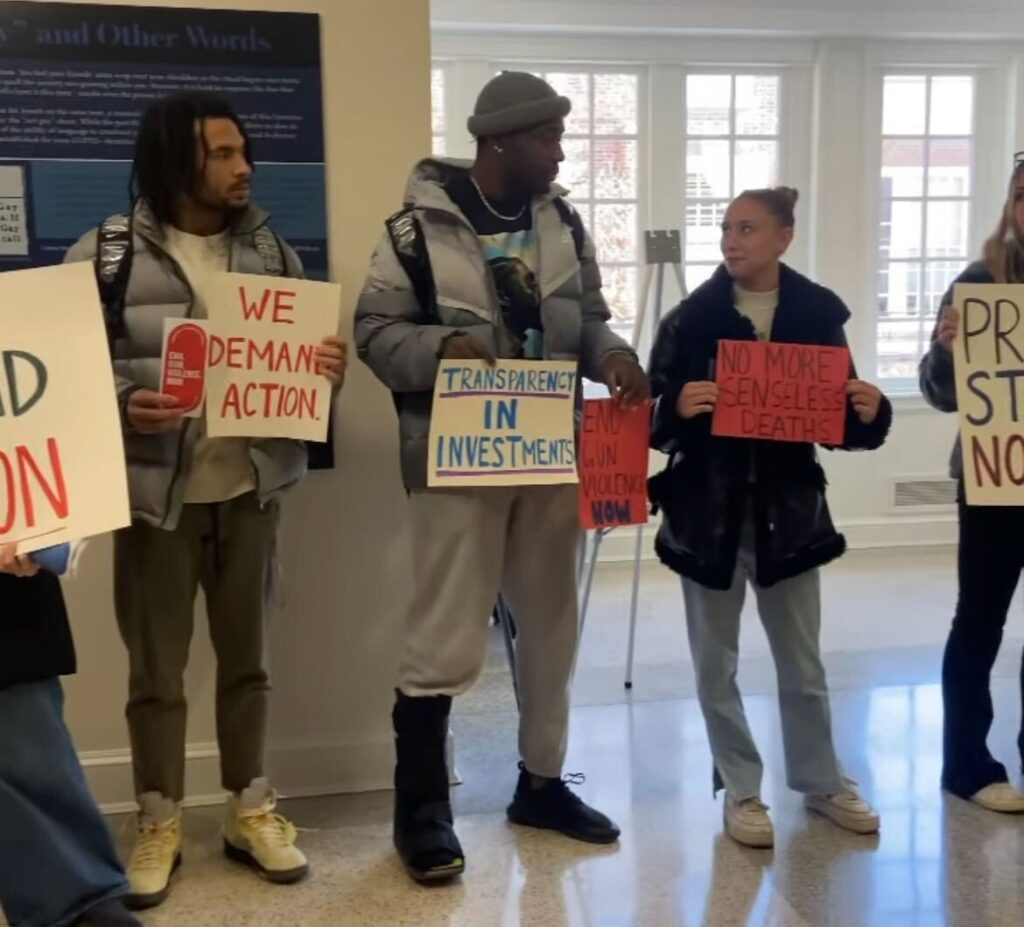

University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA. November 2023:

Student organizers at the University of Virginia (UVA) are holding a powerful rally on campus. They posted a list of demands in collaboration with other organizations on campus to call on the university to divest from the gun industry: A killer business that is raking in around $9 billion annually while gun violence devastates our country and our generation. A year prior, the University of Virginia’s campus was shaken by a shooting that led to the death of three and the injury of two UVA students.

The organizers get word that Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin—a longtime ally of the gun lobby—is at a speaking engagement and move their rally to right outside the door where he is speaking. They will make their voices heard, even at the highest levels.

This is a movement for our right to live a life free of gun violence.

Gun violence is a constant threat to our safety (on- and off-campus) and to our livelihoods. Guns are the #1 killer of children, teens, and college-aged youth in the U.S.—and the gun industry has done nothing to stop this.

The gun industry refuses to solve the problem on its own because it says protecting lives could be bad for its pocketbooks. So we continue to create adverse conditions—legal, regulatory, social, financial, or reputational—under which action by the industry becomes a logical or necessary choice for survival. Simply put, we will force them to take action.

For the past year, students at campuses across the country have been calling on our colleges, universities, and higher education institutions to divest from the gun industry’s #KillerBusiness to send them a message. And we won’t stop until there is meaningful action.

Our colleges and universities should use their money to protect their students, not to invest in the very industry claiming their lives. And that’s where divestment comes in. Read along as we take a look back at how divestment on college campuses has shaped social consciousness throughout history.

What is divestment?

Divestment is the opposite of investment: It simply means getting rid of stocks, bonds, or investment funds. Colleges and universities invest in both private and public companies, mainly through their endowments.

Endowments are large sums of money that higher education institutions use to fund things on campus such as:

- Faculty research,

- Renovating buildings,

- Financial aid and scholarships,

- And so much more.

Colleges and universities have a moral responsibility to use endowment money in a way that benefits their students. Investing in gun companies that profit off of the guns that wreak havoc on students and communities is certainly not in the best interest of students on any campus.

Divestment publicly signals a clear opposition to the gun industry’s dangerous practices.

History shows this movement works

There is a long and proven history of activism on college campuses helping to raise awareness about social injustices—think of the student sit-ins at lunch counters during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, led by four freshmen from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College, and the Black Student Strike of 1969.

Students have called on their campuses—and, through this activism, the broader United States—to make significant financial changes to pull their money out of unjust systems. In the 1970s and early 1980s, students across the nation made their voices heard as they advocated for university divestment in the face of South African apartheid. But the push for divestment from apartheid by student organizers began in 1965.

What was apartheid in South Africa?

The South African system of apartheid was a system of racial segregation officially sanctioned by the all-white government. Non-white residents of South Africa were limited in where they could travel, what roles they could work, where they could live, who they could marry, what languages they could speak, and what levels of education they could access. They were kept from voting or politically engaging in the country, and those who tried to resist the system were arrested and/or imprisoned. And even as the government became more restrictive, other countries—including the U.S.—continued to economically support South Africa.

Where it began: Anti-apartheid

In 1965, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) joined with Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to organize a sit-in and protest against the Chase Manhattan National Bank in New York City. This bank, along with other financial institutions in the U.S., was investing in South Africa and, therefore, bankrolling the unjust system of apartheid. Students and organizers wanted “[t]o bring home these implications in a sustained and systematic way” to make everyday Americans aware of the negative impact their money was having overseas.

The protest organizers “urge[d] the bank to discontinue its support of the South African government, and urge[d] depositors to cancel their accounts until that decision [was] made” by the bank. The groups also coordinated a simultaneous national action to physically protest at “the non-financial corporations that invest[ed] in South Africa.” Among other goals, this campaign sought to establish the possibility of visible, pointed action against specific targets—a strategy that continues to make up the backbone of many divestment campaigns today.

Pressure from student organizers on campuses soon followed.

Partial timeline of student action on South African divestment

1965

-

Chase Manhattan Bank

The SNCC demonstrates with SDS at the Chase Manhattan Bank

1966

-

“Disengagement”

George Houser writes a paper advocating for “disengagement” that references the 1965 actions of SNCC and SDS. This model “was the strategy that became disinvestment, and in many ways, continues to guide the movement today.”

1969

-

Princeton University

Members of the Association of Black Collegians at Princeton University organize a campus anti-apartheid sit-in, occupying a campus building to demand divestment “on moral grounds” from South Africa.

1977

-

Global Sullivan Principles

Rev. Leon H. Sullivan, an African American minister, introduces the Global Sullivan Principles—seven requirements of “social responsibility” a corporation was to demand for its employees as a condition for doing business. -

Hampshire College

Hampshire College students use petitions and handouts to call for full divestment from companies with major South African interests—one of the first universities to do so.

1985

-

UNC-Chapel Hill

The Anti-Apartheid Support Group officially forms at UNC-Chapel Hill. -

Columbia University

Student members of the Coalition for a Free South Africa at Columbia University make speeches, organize marches, and distribute materials to advocate for full university divestment, which is achieved in October. -

Cornell University

Cornell University students organize an anti-apartheid in South Africa divestment sit-in, picket, and build shantytowns as a form of nonviolent occupation on campus. -

UC Berkeley

UC Berkeley students stage a sustained sit-in and boycott classes to advocate for divestment, prompting UC Regents to divest $3.1 billion in 1986, “the largest university divestment in the country” at that time.

1986

-

Johns Hopkins University

The Coalition for a Free South Africa forms at Johns Hopkins University. Students hold protests and a 9-day sit-in to advocate for divestment. In October, JHU implements a selective divestment resolution and later fully divests from all South African corporations and companies.

1987

-

Barclays Bank

Barclays Bank officially completely divests from South Africa after years of pressure from students and protestors, including students organizing to close branches of Barclays Bank on their campuses. -

UNC-Chapel Hill

UNC-Chapel Hill officially divests in October from South African companies after students organized via protest activities that included occupying the Chancellor’s office and building a shantytown at the South Building on campus.

Sources1By timeline header: Chase Manhattan Bank; Disengagement; Princeton University; Global Sullivan Principles; Hampshire College; UNC-Chapel Hill; Columbia University; Cornell University; UC Berkeley; Johns Hopkins University; Barclays Bank; UNC-Chapel Hill

Ultimately, over 110 campuses successfully lobbied their colleges to take divestment actions against South Africa. Importantly, many more campuses saw protests and actions by students encouraging their places of higher education to divest from South Africa. And even though not all institutions listened to student voices, the legacy these organizers left continues in the movements we see today.

Ways it’s continued: Climate change

The legacy of the push for divestment from South African apartheid lies not in its economic impact, but in the tangible nature of its strategy. Divestment movements organized students and communities, giving them an action to accomplish. It showed people that small steps at a local level—protesting at universities, churches, and local governments—could ripple into a national impact as communities across the country took up the call.

In the early 2010s, students on college campuses—beginning with Swarthmore College—began calling for divestment from fossil fuel companies. In the winter of 2011 and 2012, Hampshire College (also the first school to divest from South Africa during the anti-apartheid movement) and Unity College became the first colleges in the United States to fully divest from fossil fuels.

Princeton University students took up divestment calls started by their counterparts in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, this time successfully calling upon Princeton to divest from 90 companies involved in certain segments of the fossil fuel industry in 2022.

Due in part to the push from student organizers, at least 250 education institutions2 According to the Global Fossil Fuel Divestment Commitments Database, https://divestmentdatabase.org/, accessed Jan. 23, 2024 have committed to some form of fossil fuel divestment—and the movement just keeps growing. Here again, the power of the divestment movement is found not just in the specific victories on one campus, but in the repeated ripple impact that students committed to bringing about change can enact. Each time young people organize against an institution’s investment in injustice, they publicly call attention to the crisis of climate change and work to stigmatize the actions of the fossil fuel industry.

Where it’s going: Gun industry accountability

The lessons we learn from student organizers who took action against apartheid, the fossil fuel industry, and other injustices continue into our movements today. Over the years, students have organized to call for divestment from many industries making a profit at the cost of the public. And while we’ve only highlighted a few campaigns and colleges in this blog, the divestment work of students across campuses nationwide is made possible by the efforts of all the students who came before us—particularly students of color and others from historically marginalized backgrounds.

And now, Students Demand Action is taking on one of the most pressing needs of our generation.

Last January, we launched our #KillerBusiness Gun Industry Accountability Divestment campaign. What started with students at over 20 schools has now grown to students at over 50 schools calling on colleges and universities to divest.

Our ask is simple: Don’t fund an industry whose #KillerBusiness is claiming the lives of students.

Using the tactics that students have leveraged in past divestment campaigns can help guide how we tackle our campaigns to make sure our schools divest from a gun industry’s #KillerBusiness that continues to take actions that make us less safe.

Students organized nearly 100 divestment events nationwide in 2023 and received over 2,000 petition signatures from across the country calling for divestment. We’ve met with investment advisory boards on our campuses, rallied on our campuses, passed student government proclamations, and given public comment at Regent and trustee meetings—and we’re just getting started. While progress may take some time, we are a movement of dedicated students and community members fighting to make sure we don’t continue to die at the hands of preventable tragedies.